Quantum Fundamentals: Winter-2025

Complex Number Practice (SOLUTION): Due Day 5 Th 2/14 Math Bits

- Complex Numbers: Rectangular Form

S1 5189S

For the complex numbers \(z_1=3-4i\) and \(z_2=7+2i\), compute:

- \(z_1-z_2\)

\begin{align} z_1-z_2&=(3-4i)-(7+2i)\\ &=(3-7)+(-4-2)i\\ &=-4-6i \end{align}

- \(z_1 \, z_2\)

\begin{align} z_1 \, z_2&=(3-4i)(7+2i)\\ &=21+6i-28i+8\\ &=29-22i \end{align}

- \(\frac{z_1}{z_2}\)

\begin{align} \frac{z_1}{z_2}&=\frac{3-4i}{7+2i}\\ &=\frac{3-4i}{7+2i}\,\frac{7-2i}{7-2i}\\ &=\frac{21-6i-28i-8}{49-14i+14i+4}\\ &=\frac{13-34i}{53} \end{align}

- \(z_1-z_2\)

- Circle Trigonometry and Complex Numbers

S1 5189S

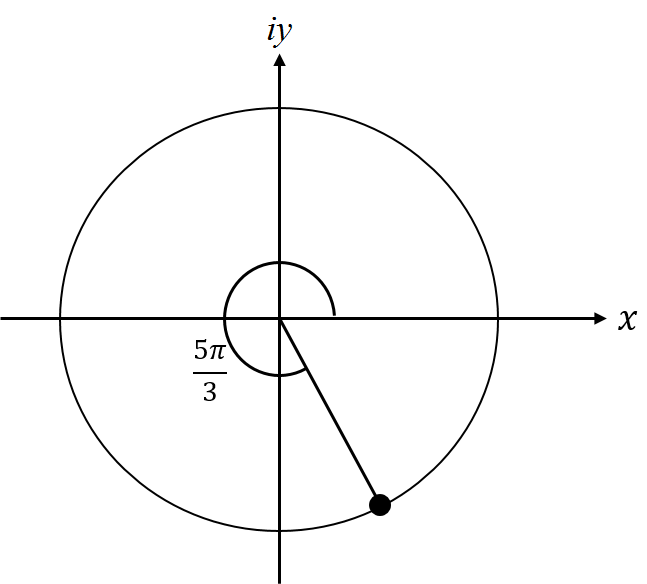

Find the rectangular coordinates of the point where the angle \(\frac{5\pi}{3}\) meets the unit circle. If this were a point in the complex plane, what would be the rectangular and exponential forms of the complex number? (See figure.)

If this were a point in the complex plane, the \(y\) coordinate would correspond to the imaginary component and the \(x\) coordinate would be the real component. I can find the rectangular form by comparing the formulae for rectangular and polar forms of a complex number:

\begin{align*} z &= x + iy\\ &= \cos\theta + i\sin\theta\\[12pt] x &= \cos\left(\frac{5\pi}{3}\right) =\frac{1}{2}\\ y &= \sin\left(\frac{5\pi}{3}\right) =-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\\ \end{align*}

This gives the complex number in rectangular form (\(x+iy\)) as

\[z = \frac{1}{2}-i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\].

The exponential form (\(re^{i\phi}\)) of the complex number would have a magnitude of 1 (since it's on the unit circle) and an angle of \(\frac{5\pi}{3}\) to give:

\begin{align*} z &= 1e^{i5\pi/3}\\ &=e^{i5\pi/3} \end{align*}

- Complex Number Algebra, Exponential to Rectangular--Practice

S1 5189S

If \(z_1=5e^{7i\pi/4}\), \(z_2=3e^{-i\pi/2}\), and \(z_3=9e^{(1+i\pi)/3}\), express each of the following complex numbers in rectangular form, i.e. in the form \(x+iy\) where \(x\) and \(y\) are real.

-

\(

z_1 +z_2

\)

It's easiest to do addition in rectangular form, so change the form at the beginning of the problem. Make sure you know the sign and cosine of special angles like multiples of \(\frac{\pi}{4}\).

\begin{align*} z_1&=5e^{7i\pi/4}\\ &=5\left(\cos \frac{7\pi}{4}+i\sin \frac{7\pi}{4}\right)\\ &=5\frac{\sqrt 2}{2}\left(1-i\right) \end{align*}

-

\(

z_1 z_2

\)

It's easiest to do multiplication in exponential form, so change the form to rectangular AFTER doing the multiplication. \begin{align*} z_1 z_2&=5e^{7i\pi/4}\, 3e^{-i\pi/2}\\ &=15e^{(7-2)i\pi/4}\\ &=15\left(\cos \frac{5\pi}{4}+i\sin \frac{5\pi}{4}\right)\\ &=-15\frac{\sqrt 2}{2}\left(1+i\right) \end{align*}

-

\(

\frac{z_2}{z_3}

\)

It's easiest to do division in exponential form, so change the form to rectangular AFTER doing the division. \begin{align*} \frac{z_2}{z_3}&=\frac{3e^{-i\pi/2}} {9e^{(1+i\pi)/3}}\\ &=\frac{1}{3}\,e^{-3i\pi/6}\, e^{-3}\, e^{-2i\pi/6}\\ &=\frac{1}{3}\, e^{-3}\, \left(\cos \frac{5\pi}{6}-i\sin \frac{5\pi}{6}\right)\\ &=-\frac{1}{6}\, e^{-3}\, \left(\sqrt{3}+i\right) \end{align*}

-

\(

z_1 +z_2

\)

- Complex Numbers, All Forms--Practice

S1 5189S

Represent the following four complex numbers in rectangular form \(a + ib\), exponential form \(|z|e^{i\phi}\) , and on an Argand diagram:

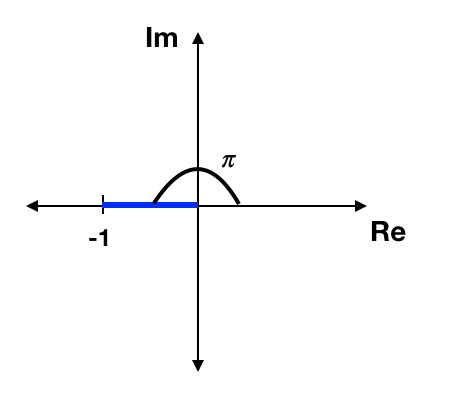

\(e^{i\pi}\)

Rectangular Form: \begin{eqnarray*} e^{i\pi} &=& \cos\pi +i\sin\pi\\ &=& -1+0\\ &=&-1 \end{eqnarray*}

Exponental Form: Already in Exponential Form!

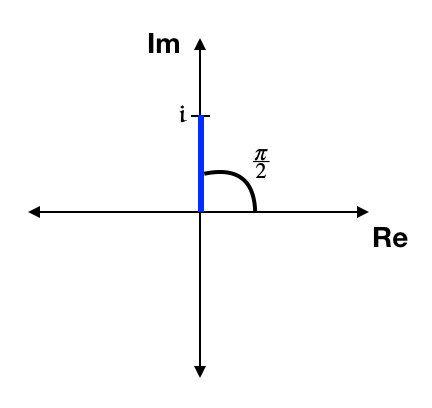

\(i\)

Rectangular Form: Already in Rectangular Form! \begin{eqnarray*} a+ib &=& 0+i(1))\\ &=& i\\ \end{eqnarray*}

Exponental Form: \begin{eqnarray*} i &=& \cos\frac{\pi}{2} +i\sin\frac{\pi}{2}\\ &=& e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}}\\ \end{eqnarray*}

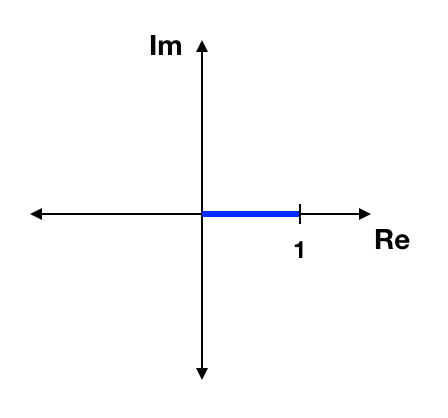

\(\sin\frac{\pi}{2}\)

Rectangular Form: Already in Rectangular Form! Just evaluate the trig function. \begin{eqnarray*} a+ib &=& \sin\frac{\pi}{2}+i(0)\\ &=& \sin\frac{\pi}{2}\\ &=& 1\\ \end{eqnarray*}

Exponental Form: The number is pure real, so the imaginary part is zero, and I need the real part to return 1. \begin{eqnarray*} \sin\frac{\pi}{2} &=& \cos(0) +i(0)\\ &=& e^{i(0)}\\ \end{eqnarray*}

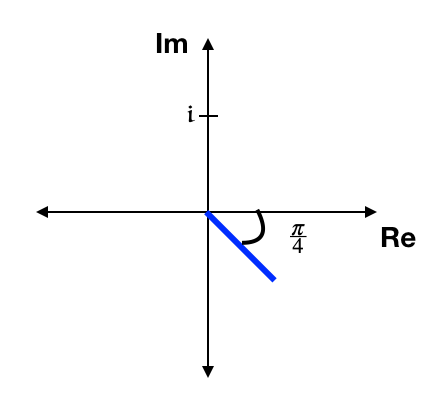

\(\cos\frac{\pi}{4}-i\sin\frac{\pi}{4}\)

Rectangular Form: Already in Rectangular Form! Just evaluate the trig functions. \begin{eqnarray*} a+ib &=& \cos\frac{\pi}{4}-i\sin\frac{\pi}{4}\\ &=& \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}-i\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\\ \end{eqnarray*}

Exponental Form: Match the pattern. I need to use the fact that sine is an odd function \(\sin(-x)=-\sin x\) and cosine is an even function \(\cos(-x)=\cos x\):

\begin{eqnarray*} \cos\frac{\pi}{4}-i\sin\frac{\pi}{4} &=& \cos\frac{-\pi}{4}+i\sin\frac{-\pi}{4}\\ &=& e^{-i\frac{\pi}{4}}\\ \end{eqnarray*}

- Exponential Form of Complex Numbers--Practice

S1 5189S

For each of the following complex numbers \(z\), find \(z^2\), \(\vert z\vert^2\), and rewrite \(z\) in exponential form, i.e. as a magnitude times a complex exponential phase:

\(z_1=i\),

\(z_1^2 = z_1 z_1 = (i)(i) = -1\)

\(\vert z_1 \vert^2 = z_1^*z_1 = (-i)(i) = 1\),

A complex number, \(z=a+ib\), in exponential form, \(z=\vert z\vert e^{i\phi}\), has a magnitude of \(\vert z \vert=\sqrt{z^*z}\). The phase can be found using tigonometry \(\phi=\arctan\left(\frac{b}{a}\right)\).

For \(z_1=i\), the number is pure imaginary and therefore is all along the vertical axis of an Argand diagram. This is an angle of \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) from the real axis in the counterclockwise direction.

This geometry also easily shows the magnitude of \(z_1\) as the distance between the origin and \(i\) on an Argand diagram is 1.

\begin{align*} \vert z_1 \vert &=1\\ \phi_1 &=\arctan\left(\frac{1}{0}\right) =\frac{\pi}{2} \\ \Longrightarrow \ z_1 &= e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}} \end{align*}

\(z_2=2+2i\),

\(z_2^2 = z_2 z_2 = (2+2i)(2+2i) = 4 + 4i + 4i -4 = 8i\)

\(\vert z_2 \vert^2=z_2^*z_2=(2-2i)(2+2i)=8\)

If plotted on an Argand diagram, \(z_2\) is in the first quadrant, and \(\phi_2\) can be determined geometrically to be \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) because the real and imaginary parts of \(z_2\) are equal.

\begin{align*} \vert z_2 \vert &= \sqrt{8} \\ \phi_2 &= \arctan\left({\frac{2}{2}}\right) = \frac{\pi}{4} \\ \Longrightarrow z_2 & = \sqrt{8}e^{i\frac{\pi}{4}} \end{align*}

\(z_3=3-4i\).

\(z_3^2 = z_3 z_3 = (3-4i)(3-4i) = -7-24i\)

\(\vert z_3 \vert^2 = z_3^*z_3 = (3+4i)(3-4i) = 25\)

Geometrically, this number falls in Quadrant IV on an Argand diagram.

\begin{align*} \vert z_3 \vert &= 5 \\ \phi_3 &= \arctan\left(-\frac{4}{3}\right) = -0.93 \\ \Longrightarrow z_3 &= 5e^{-0.93i} \\ \end{align*}

- Complex Number Algebra--Practice

S1 5189S

Express each of the following complex numbers in rectangular form, i.e. in the form \(x+iy\) where \(x\) and \(y\) are real.

\(3e^{2(1+i\pi)}\)

Use the rule for the exponential of a sum: \begin{align*} 3e^{2(1+i\pi)}&=3e^2e^{2\pi i}\\ &=3e^2 \end{align*}

\(3e^{i\pi}+3e^{-i\pi}\)

Use Euler's formula: \begin{align*} 3e^{i\pi}+3e^{-i\pi}&=\frac{2}{2} 3\left(e^{i\pi}+e^{-i\pi}\right)\\ &=6\cos\pi\\ &=-6 \end{align*}

\((1-i)^8\)

It's easiest to find large powers (and roots) of complex numbers in exponential form. \begin{align*} (1-i)^8 &=\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}}\right)^8 (1-i)^8\\ &=\left(\sqrt{2} e^{-i\pi/4}\right)^8\\ &=2^4 e^{-i8\pi/4}\\ &=16 \end{align*}

\(\left(1+i\sqrt{3}\right)^{6}\)

It's easiest to find large powers (and roots) of complex numbers in exponential form. \begin{align*} \left(1+i\sqrt{3}\right)^{6} &=\frac{2^6}{2^6}\left(1+i\sqrt{3}\right)^{6}\\ &=2^6\left(\frac{1+i\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^{6}\\ &=2^6\left(e^{i\pi/3}\right)^{6}\\ &=2^6\left(e^{6i\pi/3}\right)\\ &=2^6 \end{align*}

\(\frac{2+3i}{1-i}\)

\begin{align*} \frac{2+3i}{1-i}&=\left(\frac{2+3i}{1-i}\right)\left(\frac{1+i}{1+i}\right)\\ &=\frac{-1+5i}{2} \end{align*}

- Graphs of the Complex Conjugate

S1 5189S

For each of the following complex numbers, determine the complex conjugate, square, and norm. Then, plot and clearly label each \(z\), \(z^*\), and \(|z|\) on an Argand diagram.

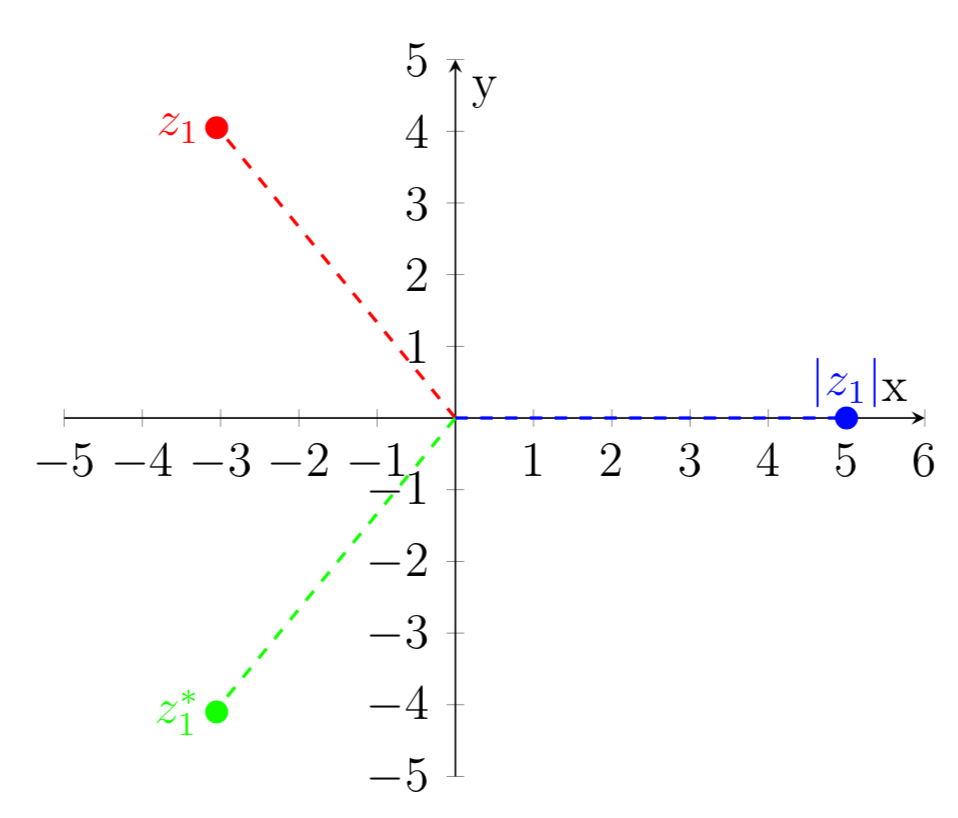

- \(z_1=4i-3\)

\begin{align} \text{Complex Conjugate:} \quad&z_1^*=(4i-3)^* = -4i-3\\ \text{Square:} \quad&z_1^2=(4i-3)^2 = 16(-1)-12i-12i+9=-7-24i \\ \text{Norm:}\quad &|z_1|=|4i-3|=\sqrt{(4i-3)(-4i-3)}=\sqrt{16+9}=5 \end{align}

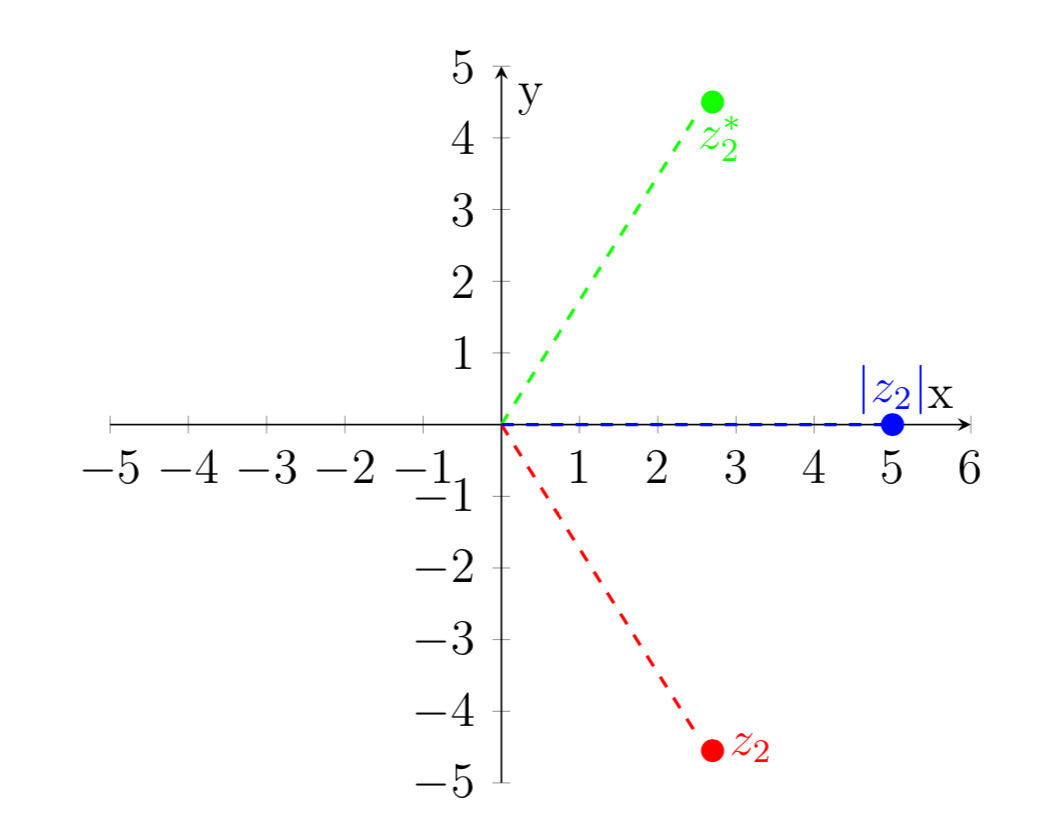

- \(z_2=5e^{-i\pi/3}\)

\begin{align} \text{Complex Conjugate:} \quad& z_2^2= (5e^{-i\pi/3})^* = 5e^{i\pi/3} \\ \text{Square:} \quad& z_2^2=(5e^{-i\pi/3})^2 = 25e^{-i2\pi/3} \\ \text{Norm:}\quad& |z_2|=|5e^{-i\pi/3}|=\sqrt{(5e^{-i\pi/3})(5e^{i\pi/3})}=\sqrt{25}=5 \end{align}

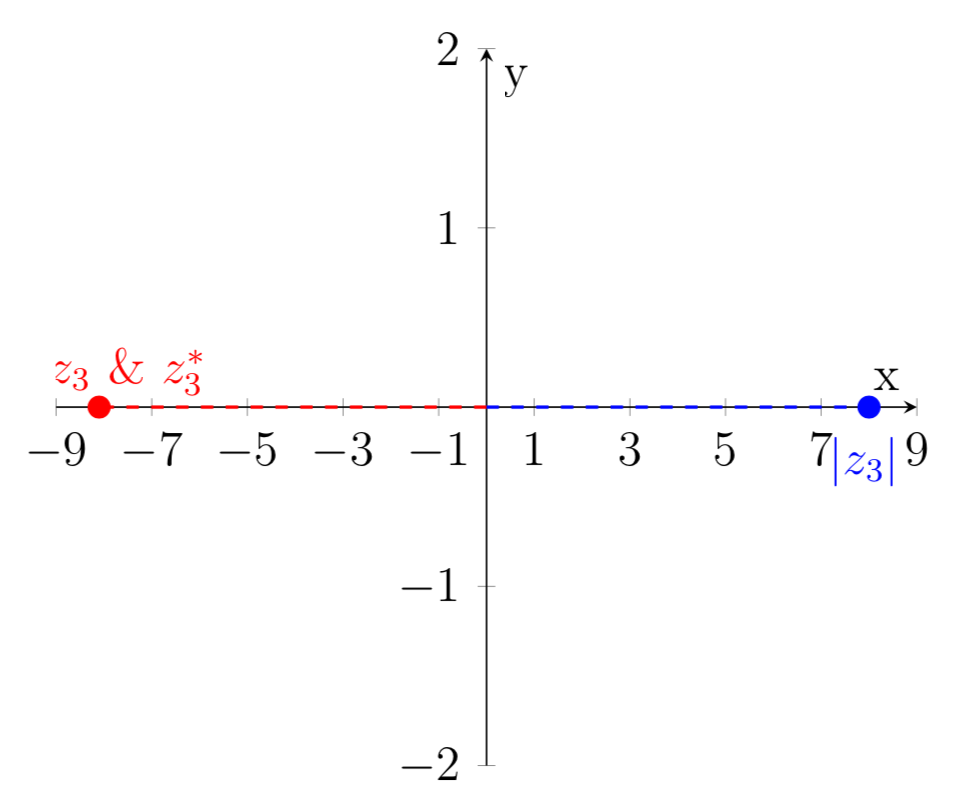

- \(z_3=-8\)

\begin{align} \text{Complex Conjugate:} \quad& z_3^2= (-8)^* = -8 \\ \text{Square:} \quad& z_3^2=(-8)^2 = 64 \\ \text{Norm:} \quad& |z_3|=\sqrt{z_3^*z_3}=\sqrt{(-8)^2}=\sqrt{64}=|-8|=8 \end{align}

- In a few full sentences, explain the geometric meaning of the complex

conjugate and norm.

The complex conjugate reflects the complex number across the real axis while retaining the distance from the origin. The operation switches the sign of any \(i\) in the complex number which causes a reflection across the real axis.

The norm is the distance from the origin to the complex number. The norm must be a real and positive because it is a length. \(z_1\) and \(z_2\) have both real and imaginary parts, but their distance from the origin is given by the norm. For \(z_3\), which is a pure real number, the norm is positive because it defines the distance the number is from zero.

- \(z_1=4i-3\)