Energy and Entropy: Fall-2024

HW 7 (SOLUTION): Due Day 23 Fri 10/25

- Rubber band lab - Ethan

S1 5077S

In this lab, we will measure the tension of a rubber as a function of length. By making this measurement at different temperatures, we will be able to use a Maxwell relation to determine the change in internal energy \(U\) and entropy \(S\) for a rubber band that is stretched at fixed temperature.

Materials:

- Rubber band

- Glass tube

- Stopper with hook

- Vernier force meter (better than spring-meter)

- Thermometer

- Several clamps

- Boiling water

- Ice

- Pan

Background

A small amount of work done on a rubber band with tension \(\tau\) and length \(L\) is \begin{equation} {\mathit{\unicode{273}}} W = \tau dL. \end{equation} This follows naturally from the definition of work as force dotted with distance---provided one takes into account the sign convention for tension, which is opposite that of pressure. Thus the thermodynamic identity is: \begin{equation} dU = TdS + \tau dL \end{equation}

We could use the thermodynamic identity directly, but since we are working at constant \(T\), it is more helpful to consider the Helmholtz free energy \begin{equation} F \equiv U - TS \end{equation}

We will use \(F\) in the analysis below.

The setup

You will stretch your rubber band between a force meter and a hook in the stopper in the bottom of a pipe. You will attach the rubber band to the force meter by means of a short chain. The rubber band will be completely immersed in water when the pipe is filled with water. This chain will enable you to conveniently change the length of the rubber band, by changing the link of the chain that is passed through the hook on the force meter.

During the experiment you will adjust the temperature of the rubber band by pouring boiling water, or ice-cold water, into the pipe. You will need to take measurements of the force as a function of length for several different temperatures. You will use a temperature probe inserted into the top of the pipe to measure the temperature of your water---and thus the temperature of your rubber band.

Collect data

You should take data of the tension as a function of length for different temperatures, over as wide a range as possible. If you can, take the same data more than once---for instance, return to your original temperature after making several other measurements---you may be able to determine whether there has been any drift.Tasks and questions

- Tension vs. length From you own data, plot the tension versus

length for a low temperature (ice cold water) and a high temperature (near 60 or 70°C).

This plot will depend on the data collected. However, you should ensure it is the correct plot and includes a title, axis labels (with units), and a legend if multiple data sets are on the same plot.

Data from literature Plot the following data*:

length (cm) \(\tau\) (N) \(\tau\) (N) @ 1.4°C @ 67°C 24.4 0.82 1.08 28.0 1.75 1.90 31.6 2.38 2.53 35.2 2.87 2.96 38.8 3.25 3.35 *Roundy and Rogers, Am. J. Phys. 81 20 (2013).

Notice that the data from Roundy and Rogers shows higher tension at higher temperature. Does your data also show this trend? If your data does not follow this trend, please use the Roundy and Rogers data for the rest of this analysis.

Ensure the plot matches with the plot from the paper and that there is a discussion comparing student data to the sample data on this plot.

- Tension vs. temperature On a new graph, plot tension versus temperature for each of your lengths. Put all the data onto a single graph. For each length, what value of \(\left(\frac{\partial {\tau}}{\partial {T}}\right)_{L}\) is the best fit to your data?

From the sample data, you would have a plot with 5 data sets with only two data points each. The quantities \(\left(\frac{\partial {\tau}}{\partial {T}}\right)_{L}\) are just the slopes of the lines between these two data points (one for each line).

Maxwell relation Starting from the defintion of Helmholtz free energy, \(F\), for a rubber band show that \begin{equation} \left(\frac{\partial {S}}{\partial {L}}\right)_{T}=-\left(\frac{\partial {\tau}}{\partial {T}}\right)_{L} \end{equation}

Hint: It will be helpful to start with the equation for \(F\), zap with \(d\), and compare with the appropriate overlord equation.

The total differential of \(F\) is \begin{equation} \text{d}F = \tau \text{d}L - S\text{d}T \end{equation} from which we can extract a Maxwell relation: \begin{align} \frac{\partial^2F}{\partial L\partial T} &= \frac{\partial^2F}{\partial T\partial L} \\ \left(\frac{\partial}{\partial L} \left(\frac{\partial F}{\partial T}\right)_L\right)_T &= \left(\frac{\partial}{\partial T} \left(\frac{\partial F}{\partial L}\right)_T\right)_L \\ -\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial L}\right)_T &= \left(\frac{\partial \tau}{\partial T}\right)_L \end{align} By measuring the variation of tension with temperature at fixed length, we can find out how entropy will change when the length is changed at fixed temperature!

- Change in \(F\), \(S\) and \(U\). Pick a temperature (for example 1.4°C), and the shortest length and longest length (for example 24.4 cm and 38.8 cm). Use your experimental data to answer the following questions as accurately as you can:

- What was \(\Delta F\) for this isothermal stretch?

Since the process is isothermal and \(dF=\tau \text{d}l - S \text{d}T\), we can show that \(\Delta F = \int \tau\, \text{d}l\). Numerically integrate the data on the \(\tau\) vs \(L\) plot. Averaging the two temperatures from the sample data, I found \(\Delta F \approx 0.34 \text{ J}\).

- What was \(\Delta S\) for this isothermal stretch?

For this, use the Maxwell relation \(-\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial L}\right)_T = \left(\frac{\partial \tau}{\partial T}\right)_L\). The RHS comes from part (3) (you get the best value if you average the slopes). Then we can approximate with the finite \(\Delta S_T \approx \left(\frac{\partial \tau}{\partial T}\right)_L \Delta L_T\), where I use the \(T\) subscript to denote that the change in entropy can be done for each temperature (since it's an isothermal stretch). Averaging \(\Delta S\) of the two temperatures for the given data, I got \(\Delta S \approx -3.3 \cdot 10^{-4} J/K\). The negative comes from the fact that, as we stretch the band, we decrease the entropy.

- What was \(\Delta U\) for this isothermal stretch?

Using \(\text{d} F = \text{d}U - T\text{d}S - S\text{d}T\), \(\text{d}T = 0\) for isothermal processes, and our result from (b) for \(\Delta S\), we can approximate \(\Delta U \approx \Delta F + T \Delta S = 0.23 \text{ J} \).

- What was \(Q\) for this isothermal stretch? (Was this energy transferred in, or out, of the rubber band?)

Using \(dS = \frac{{\mathit{\unicode{273}}} Q}{T}\), we can quickly approximate \(Q \approx T \Delta S = -0.11 \text{ J}\) using our result from (b). Heat is leaving the rubber band because, as we do work on the band by stretching it at a constant temperature, we are decreasing the entropy of the polymer.

- What was \(W\) for this isothermal stretch? (Was this energy transferred in, or out, of the rubber band?)

This can be found quickly by recalling that \(\text{d} F = \tau \text{d} l\) for this isothermal process, which is precisely the work term for the rubber band, \({\mathit{\unicode{273}}} W = \tau \text{d}l\), so as in (a) we have \(W = \Delta F = 0.34 \text{ J}\). One way we can check this is correct (or an alternate way to reach this answer) is by using the first law, \(\text{d}U = {\mathit{\unicode{273}}} W + {\mathit{\unicode{273}}} Q\), so \(W \approx \Delta U - Q\), which we find checks out perfectly.

- What was \(\Delta F\) for this isothermal stretch?

- Stat mech model of a rubber band

S1 5077S

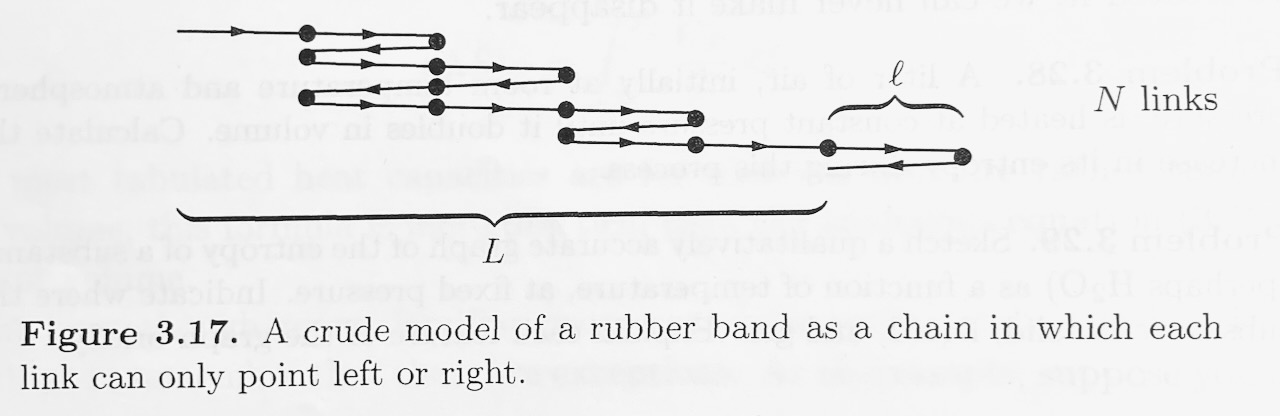

Polymers, like rubber, are made of very long molecules, usually tangled up in a configuration that has lots of entropy. As a very crude model of a rubber band, consider a chain of \(N\) links, each of length \(l\) (see Figure). \(N\) is very large. Imagine that each link has only two possible states, pointing either left or right. The total length of the rubber band is the net displacement from the begining of the first link to the end of the last link.

- Find a differentiable expression for the entropy of this system in terms of \(N\) and \(N_R\), where \(N_R\) is the number of links pointing to the right. For guidance calculating multiplicity, see Schroder's text book, \(\S\)2.1 "Two-State Systems". To write a smooth function \(S(N,N_R)\), where \(N\) and \(N_R\) are treated as continuous variables, you will need to use the idea that \(N\) and \(N_R\) are very large, and Stirling's approximation:

\begin{equation}

lnx! \approx xlnx-x \text{ , when $x \gg 1 $}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation} S=k[NlnN-N_RlnN_R-(N-N_R)ln(N-N_R)] \end{equation}

- Write down a formula for \(L\) in terms of \(N\) and \(N_R\).

\begin{equation} L=(2N_R-N)l \end{equation}

- What is the thermodynamic identity for this system (you will have to replace \(-pdV\) with something else).

\begin{equation} dU=TdS+\tau dL \end{equation}

- Using the thermodynamic identity, express tension in terms of a partial derivative of entropy. From this expression, compute the tension in terms of \(L\), \(T\), \(N\) and \(l\).

I'm looking for a partial deriviative of \(S\), so I will rearrange the thermodynamic identity so that \(dS\) is isolated on the left \begin{equation} dS=\frac{1}{T}dU-\frac{\tau}{T} dL \end{equation} Now, I compare with the appropriate overlord equation and determine \begin{equation} \left(\frac{\partial {S}}{\partial {L}}\right)_{U} = -\frac{\tau}{T}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \tau=-T\left(\frac{\partial {S}}{\partial {L}}\right)_{U}. \end{equation} Conveniently, my expression for the entropy of a freely jointed chain can be written just in terms of \(L\) (\(U\) does not appear). So I'll use the total derivative

\begin{equation} \tau=-T \frac{dS}{dL}. \end{equation}

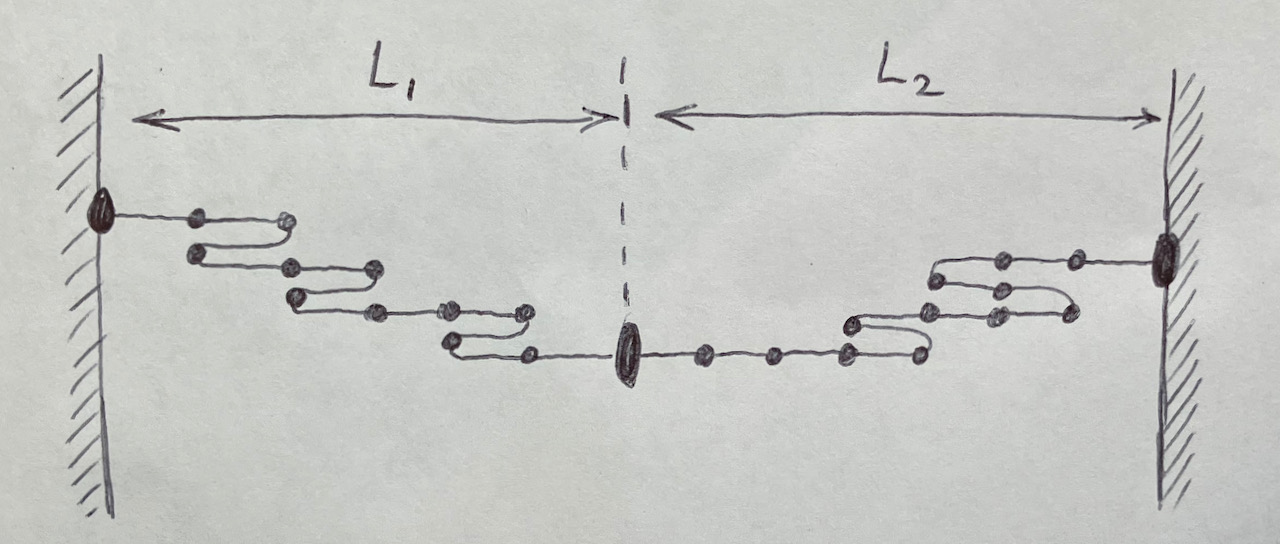

To see the connection between \(\tau\) and \(\frac{dS}{dL}\), I find it helpful to think about connecting two freely jointed chains of length \(L_1\) and \(L_2\). These freely joined chains share a thermal bath of temperature \(T\) as shown in the figure below. The total length, \(L_1 + L_2\) is fixed. The individual lengths, \(L_1\) and \(L_2\), will adjust until \(\tau_1=\tau_2\). The equilibrium point occurs when total entropy, \(S_1+S_2\), is maximized. i.e. \(\frac{dS_1}{dL_1} = \frac{dS_2}{dL_2}\). This is equivalent to saying \(\tau \propto \frac{dS}{dL} \).

Schroeder gives a simliar argument for equalizing the pressure of gas 1 and with the pressure of gas 2 when the two gases are separated by a freely moving wall inside a fixed total volume.

I'll rewrite the derivative with respect to \(N_R\): \begin{equation} \tau=-T\frac{dS}{dN_R}/\frac{dL}{dN_R}. \end{equation} To find \(dL/dN_R\), consider changing \(N_R\) by 1. This will change the overall length by \(2l\) (flipping a right pointing segment to become left pointing). So we have \begin{align} \tau&=-\frac{T}{2l}\frac{dS}{dN_R}\\ &= -\frac{kT}{2l}[-lnN_R+ln(N-N_R)]\\ &= \frac{kT}{2l}[lnN_R-ln(N-N_R)]\\ &= \frac{kT}{2l}ln\left(\frac{N_R}{N-N_R}\right)\\ &= \frac{kT}{2l}ln\left(\frac{(L+Nl)/2l}{N-(L+Nl)/2l}\right)\\ &= \frac{kT}{2l}ln\left( \frac{L+Nl}{2Nl-L-Nl}\right)\\ &= \frac{kT}{2l}ln\left( \frac{Nl+L}{Nl-L} \right)\\ \end{align}

- Show that when \(L \ll Nl\), the tension is directly proportional to \(L\) (Hooke's law)

You will need the result \(ln(1+x)\approx x\) when \(x \ll 1\).

- Discuss the dependence of the tension force on temperature. If you increase the temperature of the rubber band, does it tend to relax or tighten.

Tension increases with temperature.

- Suppose that you hold a relaxed rubber band in both hands and suddenly stetch it. Would you expect its temperature to increase or decrease? Explain.

Entropy decreases when this polymer is stretched. For a system to decrease its entropy, \(Q\) must be negative. i.e. energy must leave the system by heat transer. To drive this heat transfer, the temperature of the system must go up.

- Find a differentiable expression for the entropy of this system in terms of \(N\) and \(N_R\), where \(N_R\) is the number of links pointing to the right. For guidance calculating multiplicity, see Schroder's text book, \(\S\)2.1 "Two-State Systems". To write a smooth function \(S(N,N_R)\), where \(N\) and \(N_R\) are treated as continuous variables, you will need to use the idea that \(N\) and \(N_R\) are very large, and Stirling's approximation:

\begin{equation}

lnx! \approx xlnx-x \text{ , when $x \gg 1 $}.

\end{equation}