Energy and Entropy: Fall-2024

HW 1 (SOLUTION): Due Day 5 Tues 10/1

- Ice calorimetry lab questions

S1 5071S

This question is about the ice calorimeter lab we did in class

- Plot your data

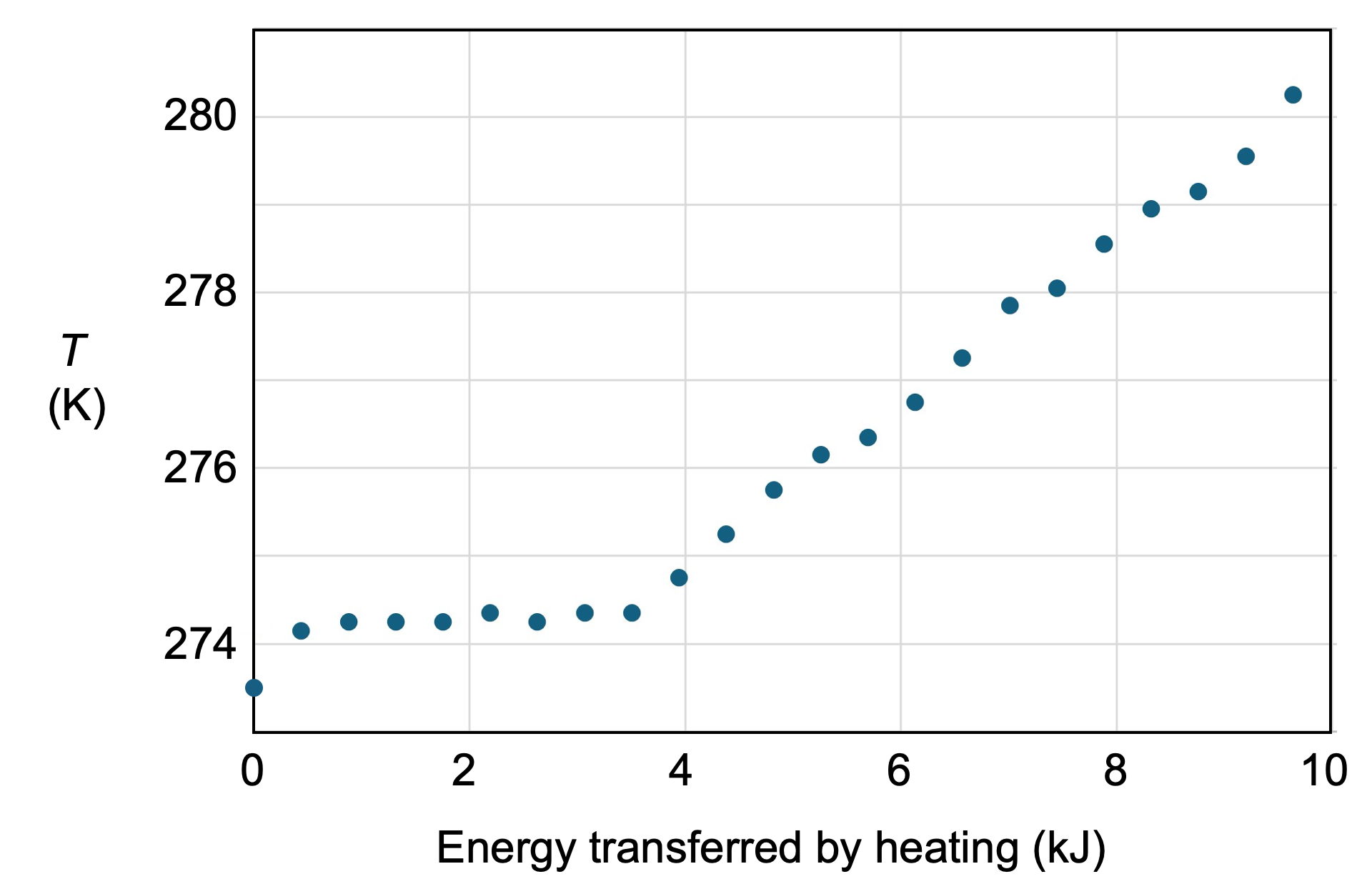

Plot the temperature of the system at time \(t\), with respect to the total energy that had been thermally added to the system at time \(t\). This thermally-added energy is called "heat". In this experiment, heat \(Q\) is increasing as a function of time. To find the net heat transferred from 0 to \(t\), you will need to integrate the power from 0 to \(t\). Discuss your \(T(Q)\) curve and any interesting features you notice on it.

The graph shows the measured temperature of liquid water while 109 g of ice melted into the liquid. The initial amount of liquid water was 192 g. Melting was driven by a resistive heater with power \(P\) = 14.6 W. Data points were acquired every 30 seconds. The system was insulated from the surroundings by a styrofoam cup.

Your results may differ slightly from this data (especially if you didn't stir the water), but key features are: (i) The system starts \(0^\circ\)C because the ice and water are in equilibrium. (ii) The heater transfers energy to the liquid which initially causes a small increase the liquid temperature. (iii) The liquid starts transferring energy to the ice and the temperature of the liquid stablizes (stays constant) while the heater is on and the ice is melting. (iv) When all the ice has melted, the temperature of the liquid starts to increase. From our data, we see that the temperature increase is apporximately linear in this final stage of the experiment.

Specific heat capacity From your data, find \(C_p\), the heat capacity of the liquid water in your cup at a particular temperature, and \(c_p\), the specific heat capacity of liquid water at a particular temperature. You can find the heat capacity by examing the slope of your \(T\) vs. \(Q\) graph. i.e. \begin{align} C_p = \frac{\text{Heat that entered the system during the temperature change}}{\Delta T} \end{align} where \(\Delta T\) is the temperature change. The S.I. units of heat capacity are joule/kelvin. The \(p\) subscript means that your measurement was made at constant pressure.How does your answer compare with the prediction of the Dulong-Petit law?

To find \(C_p\) from the experimental data, we focus on data points after all the ice has melted. It required 6 kJ of energy transfer by heating to raise the temperature 5.5°C. Thus, we find \(C_p \approx 1100\) J/K for this mass of 300 g water.

The Dulong-Petit Law posits that the heat capacity, \(C_p\), of certain substances is approximately \(\approx 3n_{\text{atom}}R = 3N_{\text{atom}}k_B\), where \(n_{\text{atom}}\) is the number of atoms (in moles) and \(R\) is the universal gas constant. 300 g of H2O contain about 16.7 moles of oxygen atoms and 33.4 moles of hydrogen atoms, so \(n_{\text{atom}} \approx\) 50 moles. Thus, we predict \begin{equation} C_p = 3 \cdot 50 \cdot 8.314 \approx 1250 \, \text{J/K} \, . \end{equation}

This is a very reasonable prediction compared to the value we expect from the published specific heat: 300 g \(\times\) 4.2 J/(K\(\cdot\)g) = 1260 J/K.

Latent heat of fusion Looking at data from a group that vigorously stirred the ice bath, what did the temperature do while the ice was melting? How much energy was required to melt the ice in the calorimeter? How much energy was required per unit mass? per molecule?

The energy transferred to the ice during the melt process was about 3.5 kJ. This energy was calculated from the power dissipated by the resistor (14.6 W), over a period of about 4 minutes (240 s).

To find the energy per unit mass needed to turn ice into liquid water, which we often call the latent heat of fusion (\(l\)), we divide \(Q_{melting}\) by the total mass of the ice (109 g in our example), \begin{equation} l = Q_{\text{melting}}/m_{\text{ice}}= 32 \text{ J/g} \end{equation}

Lastly, we wish to find the energy per molecule needed to melt the ice. To do this, we first need to calculate the number of molecules of water by making use of Avogadro's number (\(N_{Av} = 6.022 \times 10^{23}\) molecules/mole) to state that, \begin{equation} N = N_{Av} n \, , \end{equation} where \(n\) is the number of moles of H2O. The number of moles can in turn be found using the molar mass of water, \(M_{H_2O} \approx 18 \text{ g/mol}\), so, \begin{equation} n_{\text{ice}} = \frac{m_{\text{ice}}}{M_{H_2O}} = 6.1 \text{ mol} \, . \end{equation} The number of molecules is then \(N_{ice} \approx 3.6 \cdot 10^{24}\), and thus the energy per molecule is approximately \begin{equation} Q_{melting}/N_{ice} \approx 10^{-21} \text{ J}. \end{equation}

Experimental uncertainty Compare your experimental values for \(c_p\) and latent heat to published values for water. If your values are larger or smaller, discuss systematic errors in the experiment that might be responsible. What would you do differently in a follow-up experiment?

The accepted values of specific heat and latent heat of fusion for liquid water are

- \(c_p = 4.2\) J/g\(\cdot\)K

- \(l=33.3\) J/g.

The values determined from this experiment are

- \(c_p \approx 3.6\) J/g\(\cdot\)K (15% lower than the accepted value)

- \(l \approx 32\) J/g (4% lower than the accepted value)

For the measurement of specific heat, a likely source of error is the unknown energy transfer from the environment. In the analysis, I assume that the heater was the only source of energy to heat the water. However, the enviornment was approximately 20 °C, (warmer than the water), so I expect some flow of heat from the environment into water. This systematic error would make my experimental measurement of \(c_p\) lower than the actual value. To test this hypothesis, I would repeat the experiment with better insulation, for example, double nesting two styrofoam cups.

The measured value of latent heat is also below the accepted value (but the percentage error is smaller). The time required to melt the ice was shorter than the time required to raise the temperature of the liquid water. Therefore, there was less time for energy to be transferred from the environment. This might explain why the latent heat measurement was more accourate.

Entropy of fusion The change in entropy is easy to measure for a reversible isothermal process (such as the slow melting of ice). It is \begin{align} \Delta S &= \frac{Q}{T} \end{align} where \(Q\) is the energy thermally added to complete the melting, and \(T\) is the temperature in kelvin. What is was change in the entropy of the ice you melted? What was the change in entropy per molecule? What was the change in entropy per molecule divided by Boltzmann's constant?

We found \(Q_{\text{melting}} = 3.5\) kJ. As the ice melted, I assume the ice temperature was \(0^\circ\)C = 273.15 K (slighly cooler than the surrounding water which was being heated by the heater). The change in entropy of our example system is then \(\Delta S \approx 12\) J/K.

We previously found the number of molecules of ice (\(N_{\text{ice}} \approx 3.6 \cdot 10^{24}\)). Boltzmann's constant \(k_B = 1.38 \times 10^{-23}\) J/K. So we find \begin{equation} \frac{\Delta S}{N} \approx 3.6\cdot 10^{-24} J/K\\ \frac{\Delta S}{Nk_B} \approx 0.26. \end{equation}

Entropy for a temperature change Choose two temperatures that your water reached after the ice melted. Choose a reasonably large change in temperature (for example, from 2 C to 5 C). Use your experimental data to calculate the change in entropy of the water between these two temperatures.

Hint: this change is given by \begin{align} \Delta S &= \int \frac{{\mathit{\unicode{273}}} Q}{T} \\ &= \int \frac{P(t)}{T(t)}dt \end{align} where \(P(t)\) is the heater power as a function of time and \(T(t)\) is the temperature as a function of time, and the limits of integration are the final and inital times. Do this integral numerically, using your raw data (discrete time points).To calculate the change in entropy while temperature is changing, we have to account for the changing temperature. Since we are working with discrete data, I will use a numerical integral. The data points were acquired with a constant time steps of \(\Delta t\) = 30 s. The energy added during a time step is \(P\Delta t\). During the \(i^{th}\) time step, the average temperature is \(T_i\). Thus, we can write the integral formula for \(\Delta S\) as a sum \begin{equation} \Delta S = \int \frac{P(t)}{T(t)}dt = \sum_i \frac{P}{T_i}\Delta t \end{equation}

Evaluating this sum for the final 11 data points in this data set (from 276.2 K - 280.3 K), we find \(\Delta S \approx 16\) J/K.

- Plot your data

Plot the temperature of the system at time \(t\), with respect to the total energy that had been thermally added to the system at time \(t\). This thermally-added energy is called "heat". In this experiment, heat \(Q\) is increasing as a function of time. To find the net heat transferred from 0 to \(t\), you will need to integrate the power from 0 to \(t\). Discuss your \(T(Q)\) curve and any interesting features you notice on it.

- Checking for Intensiveness / Extensiveness

S1 5071S

For each of the following equations, check whether it could possibly make sense. You will need to check both dimensions and whether the quantities involved are intensive or extensive. For each equation, explain your reasoning.

You may assume that quantities with subscripts such as \(V_0\) have the same dimensions and intensiveness/extensiveness as they would have without the subscripts.

\[p = \frac{N^2k_BT}{V}\]

This doesn't make sense, because \(N\) and \(V\) are extensive, while everything else is intensive, so the right hand side is extensive, but the left hand side is intensive.

\[p = \frac{Nk_BT}{V}\]

This does make sense, which isn't a surprise because it is the ideal gas law. Both sides are intensive, because the extensiveness of \(N\) and \(V\) cancels. In addition, the units work out right, because \(k_BT\) is energy, and pressure has units of energy over volume (which is the same as force over area).

\[U = \frac32 k_BT\]

This one doesn't make sense, because the internal energy \(U\) is extensive, but \(k_BT\) is intensive. They can't be equal.

\[U = - Nk_BT \ln\frac{V}{V_0}\]

This makes sense. \(Nk_BT\) is extensive and has dimensions of energy. \(\ln\frac{V}{V_0}\) is intensive and dimensionless, so all is good.

\[S = - k_B \ln\frac{V}{V_0}\]

This doesn't makes sense. \(S\) has the same dimensions as \(k_B\), and the log is all right, but the right hand side is intensive, while entropy is extensive.

\[S = - k_B \ln\frac{V}{N}\]

This is even worse. The logarithm of volume over number is a logarithm of a dimensionful quantity, which is very bad. The right hand side also doesn't match entropy in being extensive.