Contemporary Challenges: Fall-2023

Homework 5 (SOLUTION): Due Friday 11/17

- Human Vision

S1 4745S

(Q4M.5 from textbook) Suppose you are standing in the dark and facing a \(20 \text{ W}\) LED bulb \(100 \text{ m}\) away. If the diameter of your pupils is about \(8 \text{ mm}\) under these conditions, about how many photons of visible light enter your eye every second?

The visible spectrum of wavelengths is about \(400\text{ nm}-700\text{ nm}\). The middle of this range is 550 nm, so I'll simplify my analysis by assuming all the photons have wavelength 550 nm. The energy of each photon is \begin{align} E_{a}&=\frac{hc}{\lambda_a}\\ &=\frac{(3\times10^8)(6.6\times10^{-34})}{(550\times10^{-9})}\text{ J}\\ &= \frac{2\times10^{-25}}{5.5\times10^{-7}}\text{ J}\\ &=3.6\times10^{-19}\text{ J}\\ \notag\\ \end{align}

the corresponding rates of photon emission from the 20 watt lightbulb \begin{align} R_{a}&=\frac{P}{E_{a}}\\ &=\frac{20}{3.6\times10^{-19}}\text{ s}^{-1}\\ &=5.6\times10^{19}\text{ s}^{-1}\\ \notag \\ \end{align}

The surface area of the sphere with radius \(100\text{ m}\) is \begin{align} S_1 = 4\pi 100^2 \text{ m}^2=130000\text{ m}^2 \end{align} and the area of the pupil is \begin{equation} S_2 = \pi \left(\frac{8}{2}\right)^2 \text{mm}^2=50 \text{ mm}^2 = 5\times10^{-7}\text{ m}^2 \end{equation} So the portion of the light from the bulb that enters the eye is approximately \begin{equation} \frac{S_2}{S_1} = \frac{5\times10^{-7}}{1.3\times10^5} =4\times10^{-12} \end{equation} So the number of photons that enters the eye is approximately, \begin{align} (4\times10^{-12})\times (5.6 \times 10^{19}) = 1.6\times10^8\text{ s}^{-1} \end{align}

This is easily visible to the human eye (the human eye could see a point source emitting \(1.5 \times 10^4\) photons per second).

- Hot hydrogen atom

S1 4745S

Find the wavelength of the photon emitted during a \(n= 5\rightarrow4\) transition in a hydrogen atom.

Note: The energy levels in a hydrogen atom are \begin{align} E_n = \frac{-13.6 \text{ eV}}{n^2} \end{align} where \(n = 1,\ 2,\ 3,\ ...\)Calculate \(E_4\) and \(E_5\) \begin{align} E_4 = \frac{-13.6\text{ eV}}{4^2} = -0.85\text{ eV}\\ E_5 = \frac{-13.6\text{ eV}}{5^2} = -0.544\text{ eV}\\ \Delta E = 0.306 eV\\ \end{align} To find the wavelength in nanometers, I'll use the \(hc=1240\text{ eV.nm}\): \begin{align} \lambda = \frac{1240\text{ eV.nm}}{0.306\text{ eV}} = 4050\text{ nm} \end{align}

- Wavelength from a charge on a spring

S1 4745S

Suppose a charged particle is held in position by an electrostatic spring (i.e. the restoring force on the charge follows Hooke's law, \(F= -kx\)). The mass of the charge, and the spring constant, are such that the system has a natural frequency \(\omega = 10^{16}\text{ rad/s}\) (\(\omega\) is a fixed parameter in this question, not a variable). Find the wavelength of the photon emitted during a \(n= 1 \rightarrow 0\) transition.

By solving the Schrodinger equation for this situation, we know that the energy of the charged particle (i.e. the sum of the particle's kinetic energy, plus any potential energy stored in the spring) is given by \begin{align} E_n = \hbar \omega (n + \frac{1}{2}) \end{align} where \(n= 0,\ 1,\ 2,\ ...\)

Note: Due to the shape/symmetry of the wavefunctions for particles trapped by a springlike force, optical transitions only occur when \(\Delta n = \pm 1 \).

Sense making: Try approaching this question from a classical physics perspective. What wavelength of light would we expect from a charge that oscillates at \(\omega = 10^{16} \text{ rad/s}\)?\begin{align} &E_1 = \hbar \omega \left(\frac{3}{2}\right)\\ &E_0 = \hbar \omega \left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\\ &\Delta E = \hbar \omega = (1.05\times10^{-34})(10^{16})\text{ J}\\ & \quad \quad \quad \quad = 1.05\times 10^{-18} \text{ J} \\ & \quad \quad \quad \quad = 6.6 \text{ eV} \\ & \lambda = \frac{h c}{E_{photon}} = \frac{h c}{\hbar \omega} = \frac{1240 \text{ nm eV}}{6.6 \text{ eV}} = 190 \text{ nm} \end{align} If we applied a classical analysis (no quantum mechanics), we would expect light with frequency \(\omega/2\pi\). \begin{align} \lambda = \frac{c}{f} = \frac{hc}{hf} = \frac{hc}{\hbar \omega} = 190\text{ nm} \end{align} Exactly the same result.

- Light from an electron in a box

S1 4745S

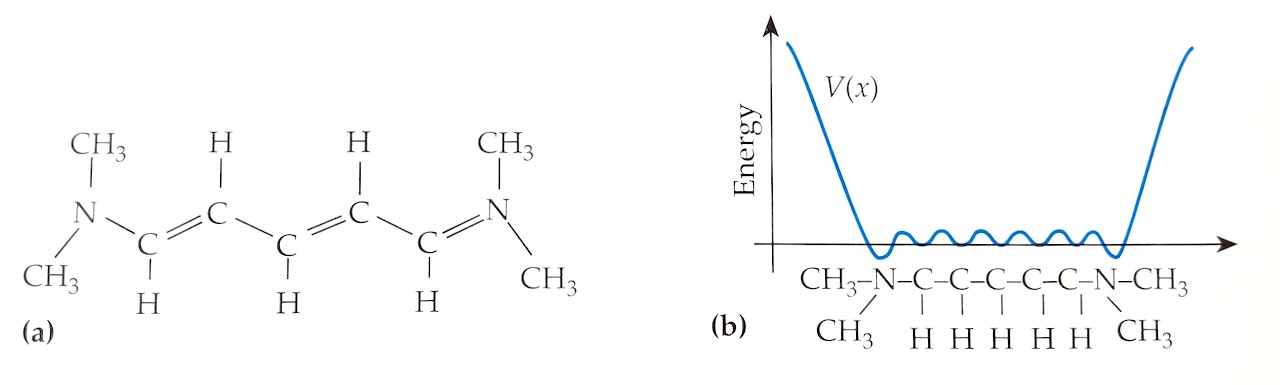

Suppose an electron is trapped in a box whose length is \(L= 1.2 \text{ nm}\). This is a coarse-grained model for an electron in a small molecule like cyanine (see Example Q11.1 in the textbook, and the figure above). If we solve the Schrodinger equation for this coarse-grained model, the possible energy levels for this electron are \begin{align} E = \frac{h^2 n^2}{8 m L^2} \end{align} where \(m\) is the mass of the electron and \(n= 1,\ 2,\ 3,\ ...\)

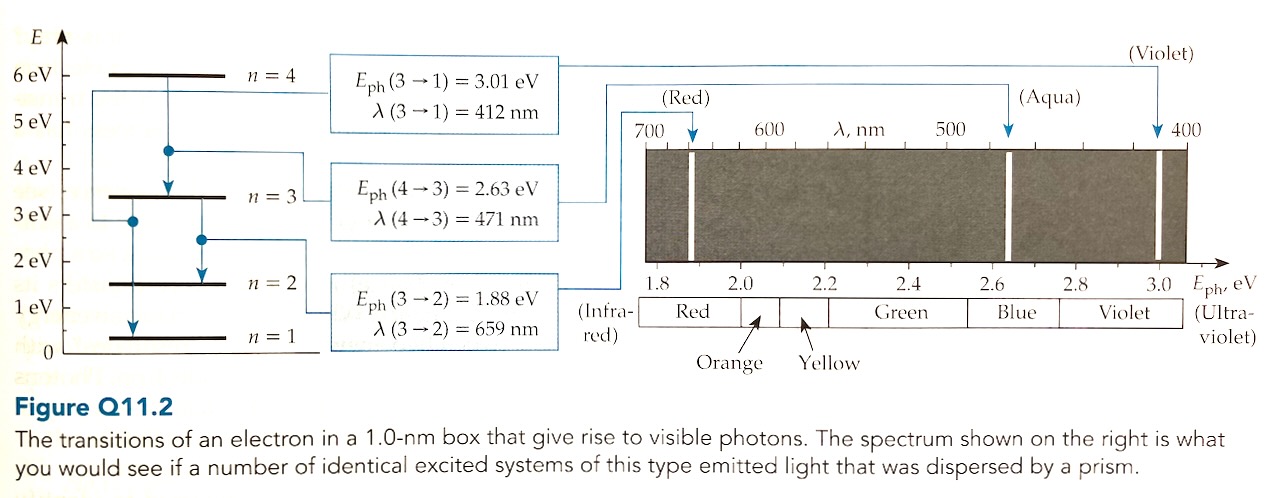

Draw a spectrum chart (like the righthand side of Figure Q11.2) to show what you would see if a number of identical excited systems of this type emitted light that was dispersed by a diffraction grating.

Note: Due to the shape/symmetries of electron wavefunctions in a box, optical transitions between energy levels only happen when \(\Delta n = n_\text{initial}-n_\text{final}\), is an odd integer.

Visible photons

The energy levels fro the electron are \begin{align} E_n &= \frac{h^2 n^2}{8 m L^2} \qquad \qquad \text{ where } L = 1.12\text{ nm}\\ &= \left[\frac{(6.6\times10^{-34})^2}{8 (9\times10^{-31}) (1.2\times10^{-9})^2}\right] n^2\\ &\approx [0.4\times10^{-19}\text{ J}]n^2\\ &=[0.25\text{ eV}]n^2 \end{align} First I'll look at transitions with \(\Delta n = 1\), for example \(n=4\) to \(n=3\).Now I'll check transitions with \(\Delta n=3\), for example \(n=4\) to \(n=1\).If \(\Delta n=5\) the system would emit photons of 3.75 eV or greater (outside the visible spectrum).In conclusion, there are four energies of visible photons that this system could emit: 2 eV, 2.25 eV, 2.75 eV and 3 eV.

- Solar Sail

S1 4745S

The first spacecraft using a solar sail for propulsion was launched in 2010. Its name is IKAROS. It has a square sail with dimensions 14 m x 14 m. Assume that the sail's mass is 2 kg and it reflects 100% of incident photons. When IKAROS is loaded with other equipment, the total mass of the vehicle is 10 kg. The sail is orientated to receive maximum light from the sun.

- Calculate the momentum of the photons that come from the sun and hit the solar sail in 1 second. Assume a solar intensity of 1300 J/(s.m\(^2\)).

- How much momentum will be transferred from solar photons to IKAROS in one day? Give a numerical answer in units of kg.m/s (assume a constant solar intensity).

- What is the change in the solar sail's velocity in one day? (assume that acceleration is only caused by sunlight).

First, find the energy hitting the solar sail in one second \begin{align} \text{Energy}=1300 \text{ J/(m\(^2\).s)} \times 1 \text{ s} \times200 \text{ m}^2 = 2.6 \times 10^{5} \end{align} \begin{align} \text{Momentum}=\frac{E}{c}=\frac{2.6 \times 10^{5} \text{ J}}{3 \times 10^8 \text{ m/s}} \approx 10^{-3} \text{ kg.m/s} \end{align}

The photons are reflected (reverse their direction), so the solar sail must receive twice the incoming momentum (for conservation of momentum to be satisfied). So, I mulltiply by 2. There are 86000 seconds in a day, so I also multiply by 86000. \begin{align} \text{Momentum transfer per day} = 8.6 \times 10^4 \times 2 \times 10^{-3} \text{ kg.m/s} \approx 150 \text{ kg.m/s} \end{align}

The spacecraft has a mass of 10 kg, so the change in velocity in one day must be 15 m/s.