Problem-Solving: Fall-2024

Tutorial 2 (Required) (SOLUTION): Due W2 D2

- Tetrahedron

S1 5140S

Using a dot product, find the angle between any two line segments that join the center of a regular tetrahedron to its vertices. Hint: Think of the vertices of the tetrahedron as sitting at the vertices of a cube (at coordinates (0,0,0), (1,1,0), (1,0,1) and (0,1,1)---you may need to build a model and play with it to see how this works!)

Think of one of the vertices of the tetrahedron lying at the origin, and the other vertices at \((1,1,0)\), \((1,0,1)\), and \((0,1,1)\). The center of the tetrahedron is at \((\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{ 2})\). Consider two vectors each pointing from the center of the tetrahedron to one of the vertices (say the first two on the list above). Then we can calculate the dot product of these two vectors in two ways: algebraically and geometrically.

\begin{align*} \left( (\hat\imath + \hat\jmath)-(\frac{1}{2} \hat\imath + \frac{1}{2} \hat\jmath + \frac{1}{2}\hat k)\right) &\cdot \left((\hat\imath + \hat k)-(\frac{1}{2} \hat\imath + \frac{1}{2} \hat\jmath + \frac{1}{2}\hat k)\right)\\ &= \left\vert \frac{1}{2} \hat\imath +\frac{1}{2} \hat\jmath -\frac{1}{2}\hat k\right\vert\left\vert \frac{1}{2} \hat\imath -\frac{1}{2} \hat\jmath+\frac{1}{2}\hat k\right\vert\cos \gamma\\ \left(\frac{1}{2} \hat\imath +\frac{1}{2} \hat\jmath -\frac{1}{2}\hat k\right) \cdot\left(\frac{1}{2} \hat\imath -\frac{1}{2} \hat\jmath+\frac{1}{2}\hat k\right) &= \sqrt{\frac{3}{4}} \sqrt{\frac{3}{4}} \cos\gamma\\ -\frac{1}{4} &= \frac{3}{4} \cos\gamma\\ \cos\gamma &= -\frac{1}{3}\\ \gamma &= \cos^{-1}\left( -\frac{1}{3}\right)\\ &\approx 109.5^o \end{align*}

This tetrahedral angle is a good approximation to the angle in a water molecule \(H_2O\), although there is lots of great chemistry/physics that goes into why the actual angle in water is somewhat less.

Sense-making: This angle is part of a triangle, so it should be less than \(180^o\). Because the two vertices of a tetrahedron are farther apart than two vertices of the cube that are adjacent to each other, the angle should be bigger than that one, which is about \(70.5^o\) (you can find this one using the same method as above!). You might also convince yourself that the triangle must be an obtuse isosceles one, as the length of each vector from the center to a vertex is \(\sqrt{3/4}\), while the length of the last leg of the triangle is \(\sqrt{2}\), which is just bigger than the value you would get from using the Pythagorean theorem as if it were a right triangle (\(\sqrt{3/2}\)).

- Distance Formula in Curvilinear Coordinates

S1 5140S

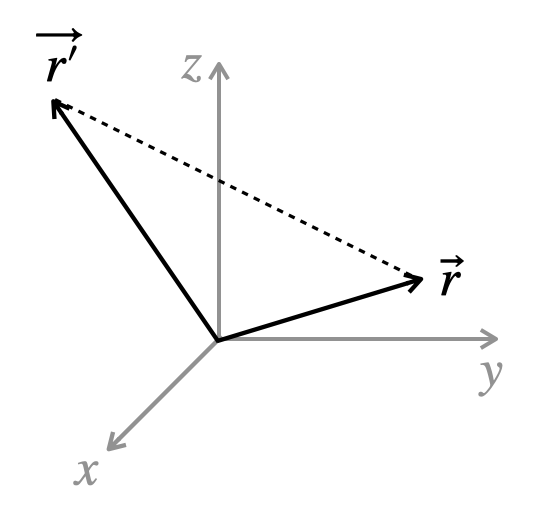

The distance \(\left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert\) between the point \(\vec r\) and the point \(\vec r'\) is a coordinate-independent, physical and geometric quantity. But, in practice, you will need to know how to express this quantity in different coordinate systems.

Hint: Be sure to use the textbook: https://books.physics.oregonstate.edu/GSF/coords2.html

Find the distance \(\left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert\) between the point \(\vec r\) and the point \(\vec r'\) in rectangular coordinates.

In rectangular coordinates: \begin{align} \left| \vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| &= \left|(x\hat{x}+y\hat{y}+z\hat{z}) -(x\,{}'\hat{x}+y\,{}'\hat{y}+z\,{}'\hat{z})\right|\\ &= \sqrt{(x-x\,{}')^2+(y-y\,{}')^2+(z-z\,{}')^2} \end{align}

Sense-making: This is the Pythagorean Theorem! The distance \(\left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert\) between the point \(\vec r\,{}'=(x\,{}',y\,{}',z\,{}')\) and the point \(\vec r=(x,y,z)\) is a coordinate-independent, physical and geometric quantity. But, in practice, you will need to know how to express this quantity in different coordinate systems.

The distance \(\left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert\) between the point \(\vec r\,{}'=(x\,{}',y\,{}',z\,{}')\) and the point \(\vec r=(x,y,z)\) is a coordinate-independent, physical and geometric quantity. But, in practice, you will need to know how to express this quantity in different coordinate systems. Show that this same distance written in cylindrical coordinates is: \begin{equation*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| =\sqrt{s^2+s\,{}'^2-2ss\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}') +(z-z\,{}')^2} \end{equation*}

In cylindrical coordinates: \begin{align*} x &= s\cos\phi\\ y &= s\sin\phi\\ z &= z \end{align*} Plug these coordinates into the answer to part (a) above. (Note: It is nontrivial to start this calculation from the position vector. Why? What is the position vector \(\vec r\) in cylindrical coordinates?) \begin{align*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| &= \sqrt{(s\cos\phi-s\,{}'\cos\phi\,{}')^2 +(s\sin\phi-s\,{}'\sin\phi\,{}')^2 + (z-z\,{}')^2}\\ &= \left[s^2(\cos^2\phi+\sin^2\phi) +s\,{}'^2(\cos^2\phi\,{}'+\sin^2\phi\,{}')\right.\\ &~~~\left. -2s\,{}' s(\cos\phi\cos\phi\,{}'+\sin\phi\sin\phi\,{}') +(z-z\,{}')^2\right]^{\frac{1}{2}}\\ &= \sqrt{s^2+s\,{}'^2-2ss\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}')+(z-z\,{}')^2} \end{align*}

Show that this same distance written in spherical coordinates is: \begin{equation*} \left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert =\sqrt{r'^2+r\,{}^2-2rr\,{}' \left[\sin\theta\sin\theta\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}') +\cos\theta\cos\theta\,{}'\right]} \end{equation*}

In spherical coordinates: \begin{align*} x &= r\sin\theta \cos\phi\\ y &= r\sin\theta \sin\phi\\ z &= r\cos\theta \end{align*} Plug these coordinates into the answer to part (a) above. (Note: It is nontrivial to start this calculation from the position vector. Why? What is the position vector \(\vec r\) in spherical coordinates?) \begin{align*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| &= \left[(r\sin\theta \cos\phi-r\,{}'\sin\theta\,{}'\cos\phi\,{}')^2\right.\\ &~~\left. +(r\sin\theta\sin\phi -r\,{}'\sin\theta\,{}' \sin\phi\,{}')^2\right.\\ &~~\left. +(r\cos\theta -r\,{}'\cos\theta\,{}')^2\right]^{\frac{1}{2}}\\ &= \left\{ r^2 [\sin^2\theta(\cos^2\phi +\sin^2\phi)+\cos^2\theta]\right.\\ &~~\left. +r\,{}'^2 [\sin^2\theta\,{}'(\cos^2\phi\,{}'+\sin^2\phi\,{}') +\cos^2\theta\,{}' ]\right.\\ &~~\left. -2rr\,{}'[\sin\theta \sin\theta\,{}'(\cos\phi\cos\phi\,{}' +\sin\phi\sin\phi\,{}')+\cos\theta\cos\theta\,{}']\right\} ^{\frac{1}{ 2}}\\ &=\sqrt{r^2+r\,{}'^2-2rr\,{}'[\sin\theta \sin\theta\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}') +\cos\theta\cos\theta\,{}']} \end{align*}

Sense-making: Wow, that is an ugly expression (don't memorize this one, by the way). Let's try some special cases. If \(\phi = \phi\,{}'\), we can use a trig identity to reduce the distance formula to \begin{equation*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| = \sqrt{r^2+r\,{}'^2-2rr\,{}' \cos\left(\theta - \theta\,{}'\right)} \end{equation*}

This is the law of cosines, which makes sense because you can easily write the angle between the two vectors in terms of the difference in the polar angles \(\theta\). The same trick doesn't work the same way for \(\theta = \theta\,{}'\), since the difference in \(\phi\) is not the difference in angles---unless \(\theta = \theta\,{}' = \pi/2\), which is on the equator (see next part).

-

Now assume that \(\vec r\,{}'\) and \(\vec r\) are in the \(x\)-\(y\) plane. Simplify

the previous two formulas.

Cylindrical Coordinates at \(z=0\) and \(z\,{}'=0\) \begin{equation*} \sqrt{s^2+s\,{}'^2-2ss\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}')} \end{equation*}

Spherical Coordinates at \(\theta\,{}'=\frac{\pi}{2}\Rightarrow \cos\theta\,{}'=0\) and \(\sin\theta\,{}'=1\). (Also true for \(\theta\).) \begin{equation*} \sqrt{r^2+r\,{}'^2-2rr\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}')} \end{equation*}

Behold the Law of Cosines once again!

- Linear Quadrupole (w/ series)

S1 5140S

Consider a collection of three charges arranged in a line along the \(z\)-axis: charges \(+Q\) at \(z=\pm D\) and charge \(-2Q\) at \(z=0\).

Find the electrostatic potential at a point \(\vec{r}\) in the \(xy\)-plane at a distance \(s\) from the center of the quadrupole. The formula for the electrostatic potential \(V\) at a point \(\vec{r}\) due to a charge \(Q\) at the point \(\vec{r}'\) is given by: \[ V(\vec{r})=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \frac{Q}{\vert \vec{r}-\vec{r}'\vert} \]

We will choose to work in cylindrical coordinates, and because we want a point in the \(xy\)-plane, we know \(z=0\), so our vector that points to where we care about measuring the potential in space, \(\vec{r}\), becomes \(\vec{r}=s \hat{s}+z \hat{z}\rightarrow s\hat{s}\).

Electrostatic potentials satisfy the superposition principle. By the principle of superposition, the potential due to the three charges is just the sum of the potentials due to the individual charges, so \(V_{total}=V_1+V_2+V_3\). Since they're all point charges, we can use the given equation for a point charge for each individual potential, \(V(\vec{r})=\frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_0}\frac{Q}{\left|\vec r-\vec r^{\prime}\right|}\). The only difference will be the charges of each contributing potential, \(Q\), and the vectors we will use that point from the origin to the charges themselves, \(\vec{r}'\).

So, we can write the total potential out like so: \begin{align} V(\vec{r})&=V_1(\vec{r})+V_2(\vec{r})+V_3(\vec{r})\\ &= \frac{1}{ {4\pi\epsilon_0}}\left\{\frac{Q_1}{\left|\vec r-\vec r^{\prime}_1\right|} +\frac{Q_2 }{ \left|\vec r-\vec r^{\prime}_2\right|} + \frac{Q_3}{\left|\vec r-\vec r^{\prime}_3\right|}\right\} \end{align} Now we just make an arbitrary decision about which number corresponds to which charge, and we let charges \(Q_1=+Q\) and be located at \(z=+D\), so that \(\vec{r}_{1}=D\hat{z}\). Similarly, \(Q_3=+Q\) and be located at \(z=-D\), so that \(\vec{r}_3=-D\hat{z}\), and finally, \(Q_2=-2Q\) and be located at \(z=0\), so that \(\vec{r}_2=(0)\hat{z}=0\). Plugging these into our whole equation for \(V(\vec{r})\), we get: \begin{align} V(\vec{r}) &= \frac{1}{{4\pi\epsilon_0}} \left\{\frac{Q}{\left|s \hat s -D\hat z\right|} -\frac{2Q}{s} + \frac{Q}{\left|s \hat s+D\hat z\right|}\right\} \end{align} Doing vector dot products to get the magnitude, we get a really fun result due to the symmetry of our problem (and the fact we're only looking on the xy-plane): \begin{align} \left|s \hat s+D\hat z\right|=\left|s \hat s-D\hat z\right|=\sqrt{s^2+D^2} \end{align} Both these magnitudes ended up being the same! And we plug this back in and we're able to simplify our potential to: \begin{align} V(\vec{r}) &= \frac{2Q}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\left\{\frac{1}{\sqrt{s^2 + D^2}} -\frac{1}{s}\right\} \end{align} Sense-making: These equations should be starting to get familiar, but checking the dimensions should remain a go-to strategy. The constants out front carry most of the dimensions, with inverse distance left---and sure enough, each term manages to have dimensions of inverse distance. Another great way of sense-making is to graph this thing and see what it looks like, which should also become one of your favorite strategies!

Assume \(s\gg D\). Find the first two non-zero terms of a power series expansion to the electrostatic potential you found in the first part of this problem.

In the first term from your answer to part (a) above, we recognize we need to use the memorized series expansion for \((1+z)^p\), which is: \begin{align} (1+z)^p= 1+pz+\frac{p(p-1)}{2!}z^2+\frac{p(p-1)(p-2)}{3!}z^3\dots \end{align} Now we can manipulate the expression by pulling out a factor of \(s^2\) from the square root: \begin{align} V(\vec r) &= \frac{2Q}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\left\{\frac{1}{\sqrt{s^2 + D^2}} -\frac{1}{s}\right\}\\ &= \frac{2Q}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \left\{\frac{1}{s\sqrt{1 + \left(\frac{D}{s}\right)^2}} -\frac{1}{s}\right\}\\ &= \frac{2Q}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \left\{\frac{1}{s} \left(1+\left(\frac{D}{s}\right)^2\right)^{-\frac{1}{2}} -\frac{1}{s}\right\} \end{align} Now it looks like \((1+z)^p\), with \(z=\left(\frac{D}{s}\right)^2\) and \(p=-\frac{1}{2}\), so we expand that term: \begin{align} V(\vec r) &= \frac{2Q}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \left\{\frac{1}{s}\left(1 -\frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{D}{s}\right)^2 +\frac{3}{8}\left(\frac{D}{s}\right)^4+\dots\right) -\frac{1}{s}\right\} \end{align} Now we distribute in the \(\frac{1}{s}\) and notice the first term cancels with the \(-\frac{1}{s}\) term: \begin{align} V(\vec r) &= \frac{2Q}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \left\{-\frac{1}{2}\frac{D^2}{s^3} +\frac{3}{8}\frac{D^4}{s^5}+\dots\right\} \end{align}

- A series of charges arranged in this way is called a linear

quadrupole. Why?

This charge distribution is called a quadrupole because the total charge and the dipole moment are both zero. In your equation, that actually means that terms in the potential that go like \(1/s\) (the "monopole" term) and \(1/s^2\) (the "dipole" term) are zero. (You have only calculated these quantities on the \(xy\)-plane, but it turns out that they are zero everywhere.) Therefore, the first (dominant) non-zero term in what's called a "multipole" expansion is the \(1/s^3\) (the "quadrupole" term). The charge distribution is called a linear quadrupole because the charges all lie in a straight line. Can you think of another (nonlinear) distribution of charges that could also be called a quadrupole? Consider a series of four charges arranged in a square with equal positive and negative charges alternating around the square.